Legend has it that the iconic star-crested mountain logo of Paramount Pictures was born in 1914 from a simple napkin doodle by co-founder W.W. Hodkinson, inspired by his childhood memories of the majestic peaks in Utah. The fledgling company’s name, the story goes, was taken from a sign on the side of an apartment building. From such humble origins, the oldest film studio in Hollywood would come to be known as the Mountain.

In recent years, this once-grand peak has seen more than its share of erosion, as Paramount has fallen behind its studio rivals and struggled to adapt to the advent of streaming. Still, with a historic lot in the heart of Los Angeles and a stable of hit franchises, including “Mission: Impossible,” “Transformers” and “Star Trek,” the Mountain remains a vital piece of Hollywood real estate worth billions, part of a media empire that also includes CBS and such cable networks as MTV and Nickelodeon. In an era of increasing consolidation, the question was not so much whether Paramount would be sold but when and to whom.

With the newly announced acquisition of Shari Redstone’s holding company National Amusements Inc. by tech scion David Ellison‘s Skydance Media in a $8.4-billion deal, the Mountain is coming under new management. Now, Paramount Pictures will embark on the next chapter in its storied history at a time of deep existential anxiety and uncertainty for the movie business as a whole.

“Given the changes in the industry, we want to fortify Paramount for the future while ensuring that content remains king,” Redstone, chair of Paramount Global and chief executive of National Amusements, said in a statement announcing the deal Sunday. “Our hope is that the Skydance transaction will enable Paramount’s continued success in this rapidly changing environment.”

For many in Hollywood, the Skydance takeover comes as a relief, given that the studio’s other bidders, Sony Pictures Entertainment and Apollo Global Management, were expected to slash jobs and further shrink the pool of buyers.

Still, Paramount’s future as a film studio remains uncertain. Ellison, who will take over as studio chief, will inherit not only its treasures but also its financial challenges, which steadily mounted over the nearly 40-year reign of the Redstone family.

The studio has already lost much of its former luster, said Stephen Galloway, dean of Chapman University’s Dodge College of Film and Media Arts.

“The Redstones took over one of the great palaces of the industry, and now they have to let it go because they couldn’t afford to maintain it,” Galloway said. “It’s goodbye to the butlers and the maids and the valets and the chauffeurs and the gardeners. Can anyone else keep the palace thriving? I don’t know. Hopefully, David Ellison has a way to do it. But the film business per se isn’t sustainable.”

Director Alfred Hitchcock on the set of 1958’s thriller “Vertigo,” one of several films he made for Paramount Pictures.

(Baron / Getty Images)

For all Paramount Pictures’ ups and downs and ownership changes over the years, its story remains inextricably tied to that of Hollywood itself.

Paramount Pictures — whose origins trace back to 1912 through the merging efforts of Adolph Zukor’s Famous Players Film Co., Jesse L. Lasky’s Feature Play Co. and distributor Hodkinson — helped lay down the crucial foundations of the nascent movie business. Its first major success, Cecil B. DeMille’s 1914 silent western “The Squaw Man,” was one of the first feature-length films shot in Hollywood. Early on, the studio placed itself at the vanguard of technological innovation, helping lead the transition out of the silent era with 1927’s World War I film “Wings,” which was released with a synchronized musical score and sound effects, and later embracing Technicolor and widescreen formats.

During the industry’s Golden Age, Paramount produced a steady stream of hits and established a roster of stars, including Marlene Dietrich, Gary Cooper and the Marx Brothers. As a brand, Paramount was associated with class and prestige; indeed, at the first Academy Awards ceremony in 1929, Paramount’s “Wings” took home the best picture prize.

In his seminal history of Hollywood’s Jewish founders, “An Empire of Their Own,” author Neal Gabler wrote that the Pararamount films of the ’20s and ’30s “purred with the smooth hum of sophistication. … The studio basked in its own daring, discrimination, taste and elan.”

“I’ve been to Paris, France, and I’ve been to Paris, Paramount,” director Ernst Lubitsch, who made a string of musicals and comedies at the studio in the 1930s, once quipped. “And frankly, I prefer Paris, Paramount.”

In 1948, Paramount suffered a major blow when the Supreme Court ruled against the studios in an antitrust case brought by the U.S. government. Along with its rivals, Paramount was forced to divest its theater operations and end the practice of vertical integration that had allowed it to control production, distribution and exhibition. Governed by settlements known as the Paramount Decrees, the decision all but drove a stake into the heart of the old Hollywood studio system and hobbled Paramount’s business.

In the mid-1960s, the studio, after being acquired by the oil and manufacturing conglomerate Gulf + Western, began a comeback under the brash leadership of former actor Robert Evans. As Evans wrote in his memoir, “The Kid Stays in the Picture,” when he took over as head of worldwide production in 1966, “There were eight major studios at the time, and Paramount was ninth.”

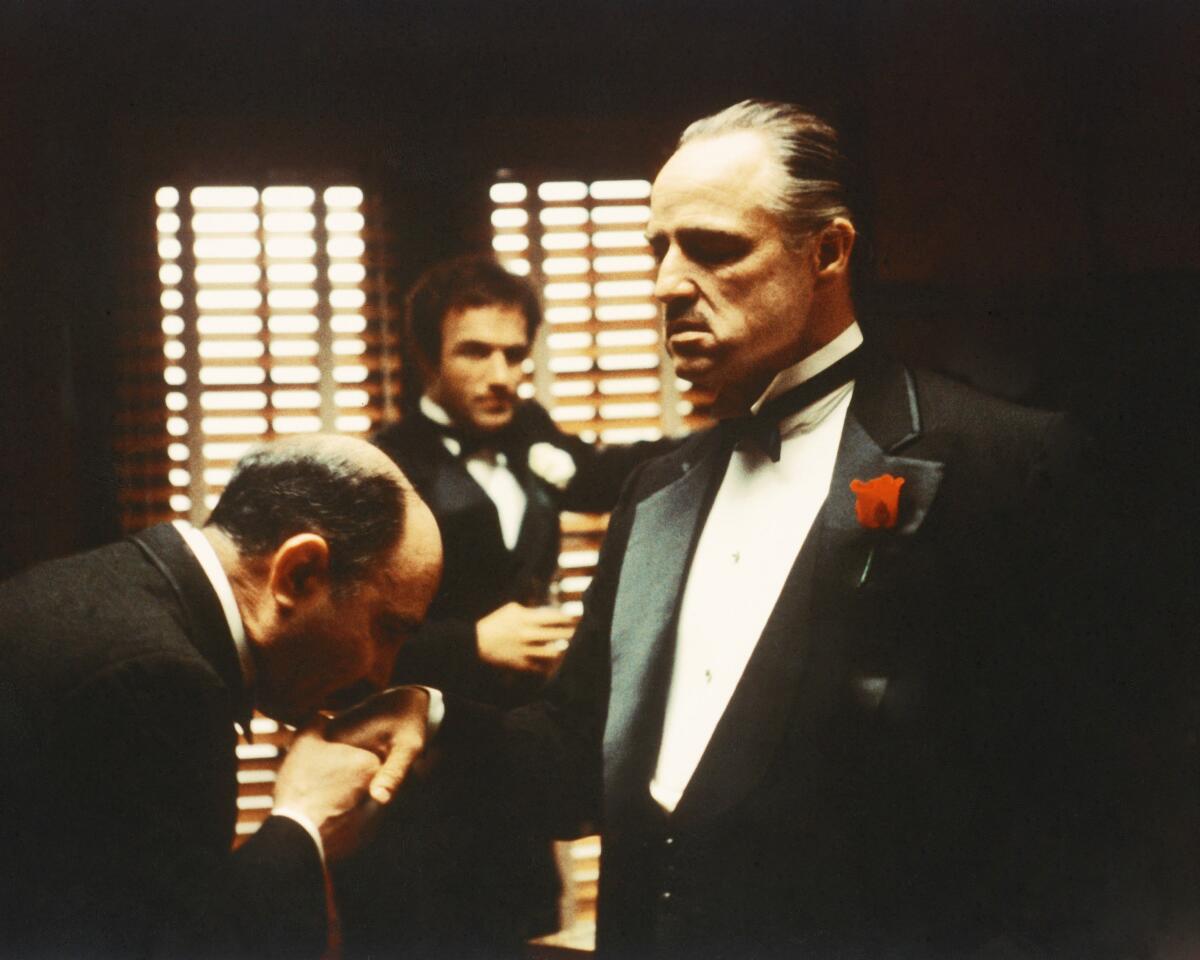

Salvatore Corsitto, left, James Caan and Marlon Brando in Francis Ford Coppola’s “The Godfather.”

(Silver Screen Collection / Getty Images)

Within a decade, Evans had reversed the studio’s fortunes and redefined its image with a string of critical and commercial hits, including “Rosemary’s Baby,” “Love Story,” “The Godfather” and “The Conversation.” In 1975, at the zenith of the Evans era, Paramount dominated the Oscars with 43 nominations, led by “Chinatown” and “The Godfather Part II,” a record for any single studio.

As the creative ferment of the 1970s gave way to the more corporate-minded culture of the 1980s, Paramount found success leveraging its “Star Trek” TV series into a string of films and generating new franchises from hits like “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” “Beverly Hills Cop,” “Friday the 13th” and “Airplane!”

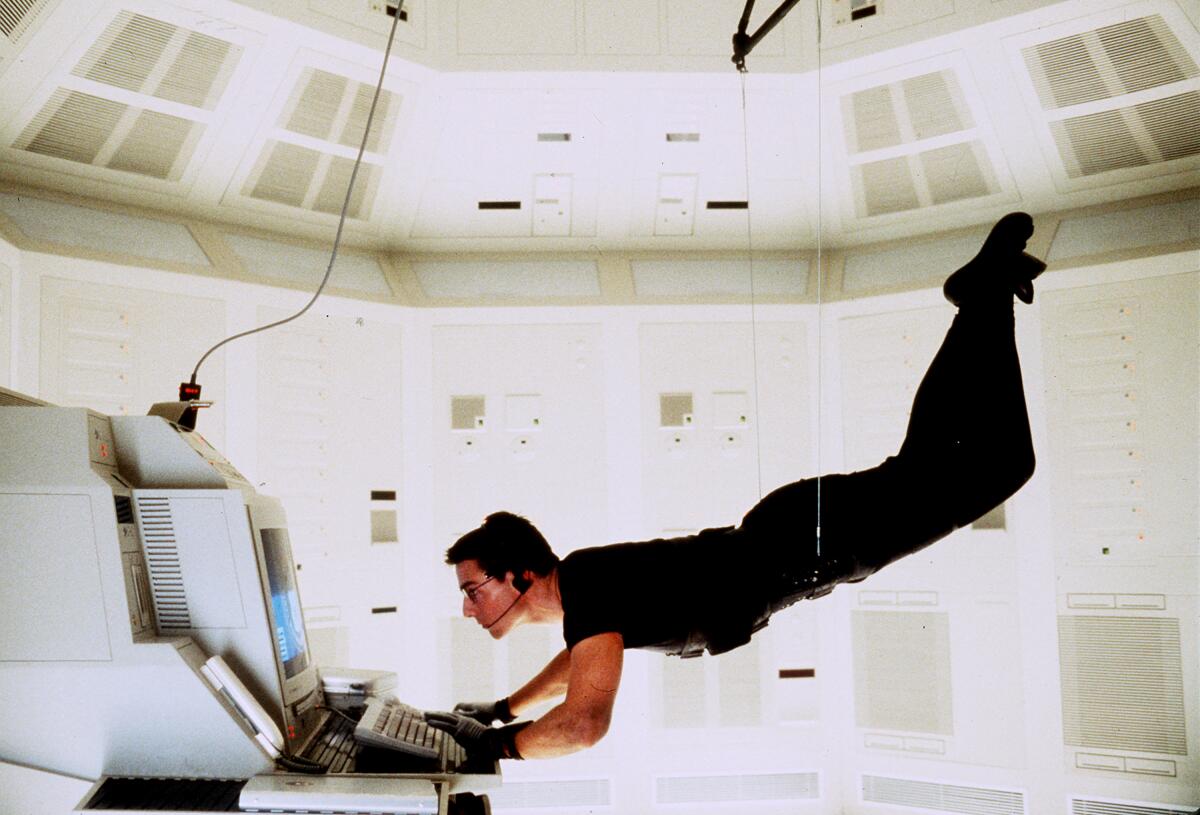

Under the leadership of Sherry Lansing, who became the first woman to head a major studio in 1992, Paramount leaned even further into broadly appealing fare like Brian De Palma’s 1996 action hit “Mission: Impossible,” which kicked off a valuable franchise that continues to this day, and James Cameron’s 1997 blockbuster “Titanic,” co-financed by 20th Century Fox, which became the highest-grossing film of all time, a record it would hold for more than a decade.

“In the ’70s, Paramount had been known as the cutting edge of a new breed of filmmaker, but Sherry had very broad, commercial, mainstream taste,” said Galloway, who wrote a 2017 biography of Lansing. “She liked character-driven dramas like ‘Fatal Attraction,’ which she had produced, and big, bold, audience-centric crowd-pleasers, like ‘Titanic,’ ‘Forrest Gump’ and ‘Braveheart,’ all of which won Oscars.”

In the years that followed, as the media and entertainment landscape began to fragment, Paramount developed a reputation for aggressively managing costs under studio chief Brad Grey and the corporate overlords at Sumner Redstone’s Viacom Inc., which took over the studio in 1994.

Paramount placed big bets on Michael Bay’s “Transformers” films and Marvel comic-book fare like “Iron Man” and “Captain America: The First Avenger,” but its slate otherwise began to grow increasingly thin. While the frugality helped boost margins, it also made Paramount less attractive among some Hollywood talent.

Over time, as the studio attempted to navigate rapidly shifting consumer habits and a volatile streaming landscape, Paramount came to be regarded as something of an also-ran. The studio has not topped the U.S. box office charts since 2011, when it pulled in $1.96 billion in domestic revenue, and the Paramount+ streaming service has struggled to compete with competitors like Netflix and Disney+.

One of Paramount’s key stars, Tom Cruise, in a scene from the 1996 hit “Mission: Impossible.”

(Murray Close / Paramount Pictures)

In pursuing Skydance’s acquisition of Paramount, Ellison — who has produced a string of blockbusters for the studio, including the 2022 smash “Top Gun: Maverick” — presented the board and shareholders a plan to pay down debt, restructure costs, invest more in the film studio and better harness data and analytics to compete in the streaming marketplace.

But for all the resilience the studio has shown over its more than 100 years in existence, the challenges ahead are more daunting than any it has faced before, and the Mountain is unlikely to ever cast as big a shadow as it once did. With box office receipts for the film industry down this year across the board, the studio has only one film on its slate this summer, the prequel “A Quiet Place: Day One,” which debuted last month with a franchise-best $53 million.

Even with Paramount’s legacy, the path for a traditional film studio has grown only more tenuous in the era of streaming.

“Look at MGM — what was once one of the most storied studios in Hollywood is now a part of Amazon with no brand identity at all,” Galloway said. “I hate to say it, but that could be the next step for Paramount. At some point, it could be the prelude to being sold to a much bigger corporation because these companies need deep pockets to compete in streaming or they’re lost.”

As fading silent star Norma Desmond famously says in 1950’s “Sunset Boulevard” — one of the many jewels in the Paramount library — “It’s the pictures that got small.”

Tag: california news | www.latimes.com